It was summer 2020. The world was struggling through the early days of COVID. Our country was gripped by the George Floyd protests. And my wife and I had hit a rough spot in our relationship. I was down in a hole. No, not a metaphorical hole like Alice In Chains’ 1992 banger (maybe you prefer the Unplugged version), but a literal hole: a dank, cramped crawlspace in Mitchell, Indiana.

Now, much of Lawrence County lies in the White River flood plain. This is low country. Also Amish country. I can’t tell you how many buggies I got stuck behind, or how many horse patties I drove through along the route. Our jobsite was a modest brick home, the homeowners an older couple looking to get their affairs in order so as not to leave their children a house in need of major repairs when their time came.

From inside the house, you would have little idea the severity of the situation down below. The floor bounced and creaked in few places, their china hutch rattling precariously as one trod through the dining room. In the main bathroom, as well as the en suite, cracking drywall could be observed in the corners. Despite the immaculate housekeeping, a musty smell persisted. These small signs presaged a far more serious situation underneath.

Aaron, my brother-in-law, had been down several months before to find the crawlspace flooded by at least a foot of water, with evidence the brackish stew had at one point very nearly reached the floor above. He left a couple submersible pumps running underneath the house in an attempt to dry the space while we finished another job. There were still a couple inches of stagnant muck when we arrived in late February.

As I said before, this is low country. Whenever it would rain, water would pour through the foundation into the crawl. Additionally, the waste pipe from the kitchen sink had been submerged so long it had corroded through. Gray water and decaying organic material emptied into this swamp, joining the fetid floodwaters. The smell was putrid. We spent most of the first couple weeks rolling around in this morass, removing from the space soggy insulation, slimy plastic sheeting, and hunks of loose concrete. The first COVID lockdowns shortly ensued and hazmat suits were impossible to find. We had to reuse the ones we had. Did I mention that this entire crawl was no more than 18-24 inches tall? The entire project involved belly-crawling through this sludge.

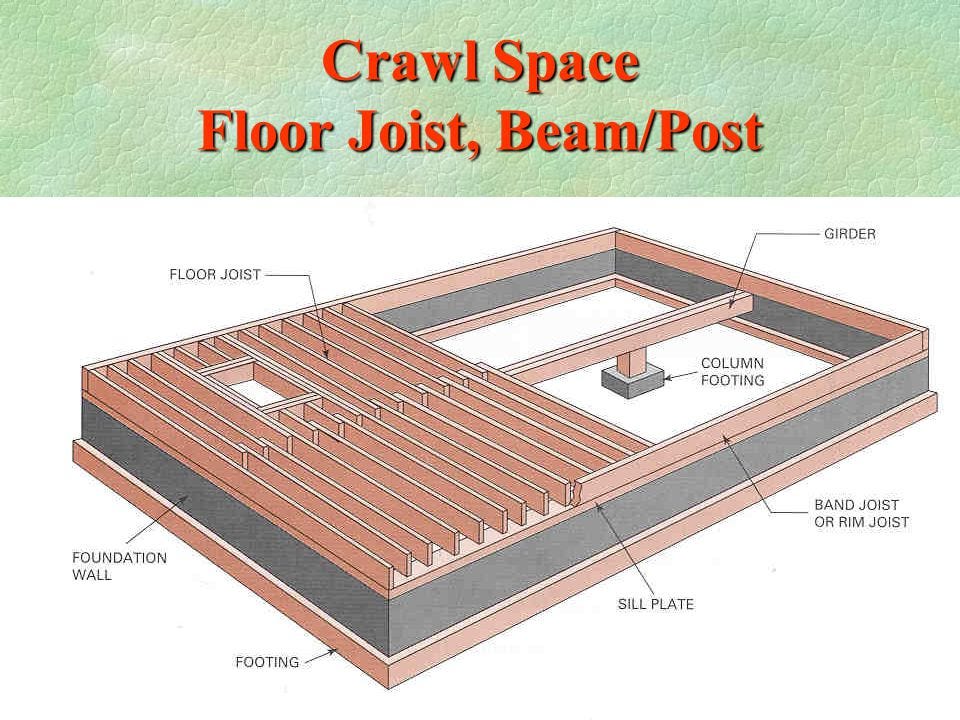

As we cleared the area of debris, finally got the last of the water out, and dried the soil with industrial air movers, we were able to explore the whole space and take in the full scope of necessary repairs. The flooding had been so extensive, so persistent, that much of the structure holding up the entire house needed to be replaced. Two-thirds of the floor joists were rotten and needed reinforced. Most of the mudsill holding the house on the foundation was decaying. And the entire support beam needed replaced. This was a major undertaking.

Aaron has a long history of structural repair work, and I had done a couple jobs with him before. We added a supplemental beam to a house in a neighborhood near Bloomington Country Club (fun story: that house had been partly held up by an old license plate). We added additional piers to a sagging beam in a house out near Ellettsville. At one point, we put a whole house near Poland on stilts so an entirely new foundation could be poured. But I hadn’t been involved in the construction industry until two years before. I was relatively new at this, and I didn’t fully understand how all the pieces worked together until this job. And while I processed this new information down in that dark hole, I gained new insight into the problems I faced when I crawled out of that pit at the end of the workday.

As I drove the 45 minutes home - not to my house, not to my wife, but to my temporary residence at a friend’s house - I began to see my relationship through the lens of structural failure. I was reading Terrence Real, John Gottman, Jared Yates Sexton, and Liz Plank. I was learning a lot about toxic masculinity and the ways our culture sets us up for failure, particularly how men are not taught to process their emotions. Me, one of the two pillars supporting my relationship, was compromised. I needed to fix myself. The foundation of our marriage was poured before either of us had the language to deal with our own trauma. I entered therapy. Soon, we began to have difficult conversations and work on systematically repairing our deep structural issues. Renovation is ongoing, but the house has never felt more solid.

And as the summer of protest went on, I saw the rotten foundation upon which our country was built, too. The racial reckoning of the Black Lives Matter protests was a time to look at the house we’ve erected on this continent, this shining city on a hill. The massive turnout across racial lines, the isolated incidents of violence, the visible discontent were the bouncing floor joists, cracking drywall, and bubbling stench pointing to signs of larger problems beneath the surface.

And peeking under there, it’s not good. It looks like there’ve been multiple renovations, attempted renovations and additions. Each time, underlying structural rot appears to have been ignored, painted over, or jerry-rigged in some fashion. It’s a miracle the thing is still standing.

I mean, look at the porous bedrock upon which this whole thing sits: white supremacy. The entire development that is Western Civilization, the Americas, the New World, rests on the belief that white, European colonizers were superior and had the God-given right to exploit the continent. Columbus laid the cornerstone and succeeding waves of explorers, invaders, and settlers haphazardly pieced together the foundation over the next 250 years.

Spanning the width of this American house is our Constitution, a three-ply laminated beam (executive, legislative, and judicial layers), upon which the various laws (joists) sit. But that is a long span, holding tons of weight. It must be supported by piers at regular intervals. And the two pillars propping up our constitutional system, the wealth by which the nascent nation was built, were the genocide of this continent’s Indigenous peoples and the system of Black chattel slavery.

The sagging, the cracking, the creaking were noticeable from the beginning, but this old house stood tall for generations before near-total collapse. A major renovation project - Reconstruction - commenced in 1865, but was abandoned before completion. Important supports were added to prop up the beam (the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments) as the pillar of slavery was removed, though the other pillar - the systematic plunder of the continent’s wealth by gunpoint - remained.

Further generations passed. The number of occupants grew considerably. Important repairs were made. Some projects commenced and were later scrapped. The 1930’s saw an entire floor added. This important expansion brought a degree of comfort to many of the dwellers (though not all). Little, however, was done to shore up the increasingly dire situation below.

The 1960’s saw continued construction above the surface, placing additional strain on the structure while only a few minor tweaks were made beneath. Still, for the most part, everything held. Most of the tenants were relatively comfortable. Until about 1980.

The 1980’s saw new management acquire the property. Maintenance was subcontracted out to private vendors. It appears some of their guys stripped a bunch of the copper wiring. Lead pipes need replaced. Tenants pay exorbitant amounts for smaller and smaller living quarters as more and more rooms sit unoccupied, turned into profitable Airbnb rentals only used part-time. Invasive pests overwhelm the senses with their Musk. Sure, she cleans up good with a little landscaping. Still plenty of curb appeal. But, make no mistake, without exorbitant bribes to the assessor, this place will not pass inspection.

Climb with me back out of this metaphor and into that crawlspace. In order to replace the support beam, Aaron and I had to construct a temporary replacement. Methodically, not more than a few feet from the original, we built a facsimile. Inch by inch, we relieved the sagging, rotting, failing beam of its burden, transferring the weight of the house onto the provisional support. With this done, we were able to remove the decaying timber, construct a new beam, and secure it in place. Only then could all the joists be reinforced. Finally, we dug a trench around the entire perimeter of the crawlspace, laid corrugated pipe, and installed a sump pump, vapor barrier, and humidity controls to keep water from becoming a problem ever again. We saved that house.

Saving our country is going to be similar. Addressing the rot is necessary. If left unattended, the house WILL collapse. But there are people living here. Human beings with lives and families, hopes and dreams, fears and aspirations. It is not feasible to relocate all the residents while the structural repairs are completed. So we must LIFT EACH OTHER up, while simultaneously working to isolate and remove the rot from our system. New materials and new techniques can help ensure the structures we build will last generations into the future, but breaktime is over. Let’s get to work now.

Thank you for writing this- and for the candor and introspection it required.

I feel like I need to shower and listen to 90s grunge (not necessarily in that order) but/and am excited to read the next post.